VAGINAL VAULT PROLAPSE / VAGINAL VAULT SUSPENSION

WHAT IS VAGINAL VAULT PROLAPSE?

Many women are told their vagina is falling out and they are terrified to hear this! The truth of the matter is that if anything is bulging out of the vaginal opening, ie a cystocele (bladder dropping), a rectocele (rectum bulging into or out of the vagina) or the top of the vagina falling, it is all vagina that is dropping and coming out! The vaginal walls are what supports these organs, therefore if the bladder is bulging out of the vagina, it is the anterior vaginal wall that is coming down and out with the bladder right behind it…what you see is the vaginal wall, not actually the bladder itself!

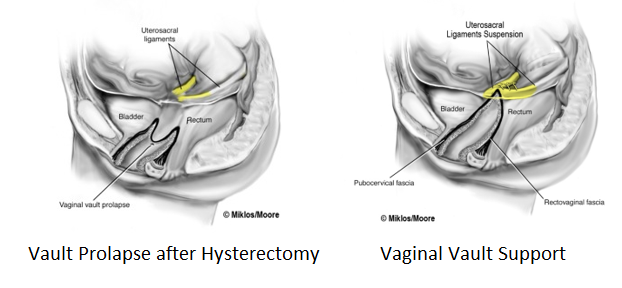

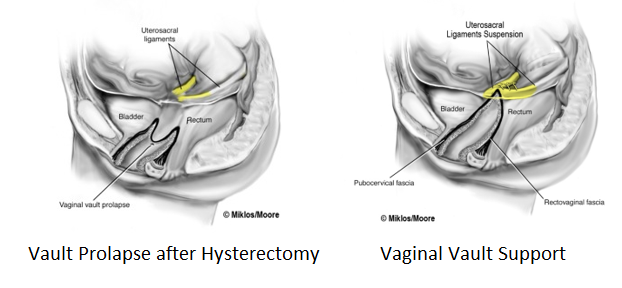

Vaginal vault prolapse refers to the upper third of the vagina falling down the vaginal canal or outside of the vagina in more severe cases. There are 3 areas that provide pelvic floor support and can prolapse or fall, ie #1- the anterior vaginal wall which supports the bladder, #2- the posterior vaginal wall that supports the rectum and #3- the apex/top of the vagina or upper 1/3 of the vagina. This area is also referred to as the Vaginal Vault. Following hysterectomy, the ligaments that support the top of the vagina after the uterus is removed can fail and this can cause the vaginal vault to prolapse. It usually does not happen by itself, ie usually it is associated with the bladder dropping (a cystocele) or the back wall bulging out of the vagina (rectocele) and it is vital at time of repair to repair ALL defects in the pelvic floor at the same time for optimal outcomes. The name of these ligaments are Uterosacral Ligaments and they support the uterus if it still is in place and after hysterectomy they support the top of the vagina. Childbirth and/or aging can cause these ligaments to weaken and/or eventually stretch out or tear causing the uterus or top of the vagina to fall. If the uterus is still in place this is called Uterine prolapse (click here for more information) however if the patient has had a hysterectomy and no longer has a uterus, it is call Vaginal Vault Prolapse. It is important to know that hysterectomy by itself does not cause vaginal vault prolapse, the ligaments themselves were damaged at some point and eventually don’t hold on to the top of the vagina any longer. This damage may be caused by vaginal childbirth and/or the aging process.

Symptoms of Vaginal Vault Prolapse

Symptoms of vaginal vault prolapse are very similar to cystocele or rectocele including pressure, pain or discomfort in the vagina and/or pelvis, low back discomfort, urinary urgency/frequency, urinary leakage, pain with intercourse and bowel dysfunction in the form of difficulty in emptying the rectum during bowel movements. The ligaments that support the top of the vagina (ie the uterosacral ligaments) originate in the sacral spine area and therefore if the vaginal vault is falling, these ligaments are stretched or torn and a woman may suffer from low back discomfort from the prolapse. Some women also have pain in the lower part of the abdomen, especially at the end of the day if they have been on their feet a lot during the day secondary to the fact that the prolapse can worsen through the day and cause more symptoms at the end of the day. Some women find relief by getting off their feet or laying down, which helps take the pressure off of the pelvic floor. If there is a hernia at the top of the vagina, this makes the prolapse larger as the skin stretches and on occasion the intestines will bulge into this hernia. This is referred to as an Enterocele and many times is associated with vault prolapse and is repaired at the time of vault prolapse repair.

Treatment Options for Vault Prolapse

If the vault prolapse is mild and not causing any symptoms, it can just be monitored and observed until it starts causing symptoms. Conservative or non-surgical therapy includes pelvic floor physical therapy which includes specialized training in Kegel or pelvic floor muscle exercises, electric stimulation, biofeedback, bowel/ bladder control strategy and other treatment modalities that can help reduce symptoms, however they will not cure the prolapse. Another non-surgical option is a pessary. A pessary is a rubber or silicone donut shaped device that is placed inside of the vagina to support the prolapse. It must be big enough to stay in the vagina and support the prolapse, but not too big to cause discomfort. Most women use pessaries as a temporary solution to the prolapse or if their health is too poor for surgical correction.

Surgical Treatment Options for Vault Prolapse

VAGINAL APPROACH

A vaginal approach may be utilized to correct vaginal vault prolapse. Larger prolapse may be more amenable to an abdominal approach, however a vaginal approach may be utilized by some surgeons no matter how large the prolapse is. The benefits of a vaginal approach is that the surgery can be completed entirely through the vagina and no incisions are needed in the abdomen. The surgery may also be completed under a spinal or epidural anesthesia and therefore risks of general anesthesia are avoided. There are several vaginal vault suspension procedures that may be utilized to support the top of the vagina at the time of prolapse surgery through a vaginal approach including Sacropinous Ligament Suspension, Uterosacral Ligament Suspension and Ileococcygeus Vaginal vault suspension.

Sacropinous Ligament Suspension (SSLF)

This is one of most common surgical procedures completed to suspend the top of the vagina. It is completed through a vaginal approach. The procedure can be completed at the same time as cystocele or rectocele repair as well as sling procedures for urinary leakage. The sacrospinous ligament attaches the spinous process of pelvic bone to the sacrum. It is a very strong ligament and provides an excellent attachment point for sutures to be placed through it to suspend the top of the vagina. It may be completed on just one side, or may be done on both sides, ie a bilateral SSLF. The ligament is deep in the pelvic and is dissected down to through a vaginal incision. It is isolated by palpation or visualization and an instrument is utilized (such as the Capio device) to place a suture through the ligament. The suture or sutures are then placed through the tissue at the top of the vagina and then tied down, which elevates the top of the vagina very nicely. The surgeon needs to be careful on the placement of the suture through the ligament however as the pudendal nerve and vessels run close to the ligament and may be injured during the placement of this suture.

Risks of SSLF including bleeding, injury to bladder or rectum (rare), nerve injury to pudendal nerve causing buttock or pelvic pain that does not improve after surgery (rare and needs surgical treatment to release the suture that is causing the pain) , bladder or bowel dysfunction, pain with intercourse (1-2%), hematoma or infection post-operatively (<1%), and failure or recurrence of prolapse (SSLF has 80-90% cure rate in most studies).

Uterosacral Ligament Suspension

The uterosacral ligaments are the ligaments that support the uterus and after hysterectomy may be utilized to suspend the top of the vagina. They are accessible abdominally or through the vagina after hysterectomy. It is a common procedure to complete during vaginal hysterectomy. The uterus is removed and then the uterosacral ligaments are identified, sutures placed through the ligaments and then attached to the top of the vagina and tied down. This elevates the vaginal apex up into the pelvis. If the patient does not have a uterus (ie prior hysterectomy) the uterosacral ligaments are more difficult to access through the vagina and therefore many surgeons will use the sacrospinous ligaments for suspension in this case.

Risks and cure raes of Uterosacral ligament suspension are the similar to SSLF above, however, there is a higher risk of kinking or blocking the ureters or the tubes that connect the kidneys to the bladder(10-15% risk per a Duke University study). The surgeon must look into the bladder after the procedure with a cystoscope to ensure that tubes or ureters are not blocked and urine is flowing into the bladder. If not, the suture causing the blockage must be removed. Pudendal nerve injury is still a risk, however a lower one as the Pudendal nerve is further away from the uterosacral ligaments compared to the SSL.

ABDOMINAL APPROACH FOR VAGINAL VAULT SUSPENSION

An abdominal approach may be utilized to suspend the top of the vagina at the time of hysterectomy or if hysterectomy has been previously performed. Some studies have shown that the abdominal approach has a higher cure rate for more severe prolapse when compared to the vaginal approach, especially if mesh is used (Sacralcolpopexy). Surgery may be completed through an open abdominal incision, however currently most surgeons will utilize a minimally invasive approach with a laparoscopic or robotic approach. This involves making tiny or mini-incisions in the abdomen and placing a camera through one of these incisions hidden in the belly button and completing the procedure through these small incisions. Advantages include outpatient type surgery, fast recovery, decreased pain, decrease risks of infection and other post-operative complications. Hospital stay is typically 24 hours or less and recovery at home is 1-2 weeks. There are two major procedures that are completed abdominally, one that uses the patients own tissue/ligaments (Uterosacral Ligament Suspension) and the other that utilizes mesh to suspend the top of the vagina (Sacralcolpopexy).

Uterosacral Ligament Suspension

The Uterosacral ligament suspension is procedure that utilizes the patients own native tissue, ie the uterosacral ligaments to suspend the top of the vagina. The procedure can be completed through the vagina (as above) however many will argue that an abdominal approach is more effective as the surgeon can visualize the ligament better and place the suture higher in the ligament which should be a stronger area of the ligament compared to the area that has failed down near the top of the vagina. This is called a high uterosacral ligament suspension or occasionally a high McCall suspension. There also should be less of a risk of causing a blockage of the ureters (tubes from the kidneys to the bladder) as they can be visualized from the abdominal approach. With a laparoscopic or robotic approach, the view is actually magnified on the screen, therefore making visualization of vital organs, such as the ureters, much easier. A suture is placed through the mid to upper section of the ligament and then it is placed through the top of the vagina and tied down. This is repeated on the opposite side and elevates the top of the vagina up into the pelvis in an anatomically correct position. Two to three sutures are placed through each ligament to complete the suspension. Cystoscopy (ie looking into the bladder with a camera) is completed at the end of the procedure to ensure that the tubes from the kidneys to the bladder (the ureters) were not blocked or kinked during the procedure. A dye is given through the patient’s IV or a pill is taken prior to surgery which turns the urine a different color and therefore the urine should be seen jetting out into the bladder on each side. If one side or the other is not working, then the sutures on that side must be removed to relieve the blockage. The uterosacral ligament suspension is best suited for mild to moderate prolapse or for those women who wish to avoid mesh for their surgery. Other prolapse surgery can also be completed abdominally at the time of the suspension including bladder suspension (paravaginal repair) or non-mesh surgery for urinary leakage ie the Burch Colposuspension. The procedure can be completed at the time of hysterectomy or can also be completed if the patient already had previous hysterectomy. The quality of the ligaments will change with the extent of the prolapse (ie the older the patient and the larger the prolapse, the weaker the ligaments will be).

Cure rates for the Uterosacral ligament suspension are in the range of 70-90% depending on the extent of the prolapse. Stage 2 or early stage 3 prolapse will have higher cure rates compared to larger prolapse and therefore as the prolapse becomes more larger or severe, that is when mesh procedures such as Sacralcolpopexy come into consideration as the cure rates are much higher.

Risks of Uterosacral ligament suspension have been reviewed in the vaginal section but in brief include: Ureteral injury, obstruction or blockage (1-2%), bowel or bladder injury (<1%), pelvic nerve injury causing short or long term pain (<1%), scar tissue causing pain at top of vagina with intercourse (<1%), and other general risks of surgery such as bleeding, hematoma or infection (all <1%). Ureteral injury is less with the abdominal/laparoscopic/robotic approach as the ureters can be visualized directly prior to placing sutures into the uterosacral ligament and therefore decreasing the risk of blocking or injuring the ureters. Additionally, the ureters should always be checked with cystoscopy (camera in the bladder) to ensure they are not blocked. If found blocked, the sutures are immediately removed and replaced in a safer location.

Abdominal Mesh Sacralcolpopexy

Mesh sacralcolpopexy is the procedure of choice for moderate to severe vaginal vault prolapse. It is a procedure that has been in use for over 40 years and has been time-proven to be safe and effective. It only makes sense that if the ligaments that once supported the uterus and/or top of vagina have failed, they may not have adequate strength to hold up the vagina in a repair. As reviewed above, failure rates for uterosacral ligament suspension increase as the prolapse gets larger, therefore surgeons have turned to mesh to support the apex or upper 1/3 of the vagina. The cure rate for abdominal sacralcolpopexy is over 90-95% and has the highest cure rate of any procedure for apical or vault prolapse.

Illustration- side view of mesh sacralcolpopexy end of procedure

Concerns over Mesh use in Pelvic Surgery: Is Mesh Safe for women with prolapse?

Mesh use in pelvic surgery has undergone recent scrutiny given the FDA Safety Notification released in 2011 (http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm) concerning mesh use for prolapse and incontinence. However, in the investigation that FDA completed following the notice, they found Mesh Use Abdominally, ie such as in sacralcolpopexy, to be safe and effective and recommended no restrictions on the procedure or any further studies required. They found that the procedure has been studied extensively with high level research trials for over 20 years and is still considered a gold standard treatment option for vaginal vault prolapse. These investigations were completed in 2014 and updated in 2017 and the FDA posted their final recommendations on their website in 2017 (https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/UroGynSurgicalMesh/default.htm) .

The American Urogynecologic Society as well as the American Urologic Association subsequently released a position statement (https://www.augs.org/assets/1/6/Position_Statement_Surgical_Options_for_PFDs.pdf) regarding abdominal mesh use for prolapse surgery and concluded:

“6. Any restriction of mesh placed abdominally for the treatment of prolapse is clearly not supported by any professional organization or the FDA.”

“To clarify, the 2011 FDA warning only reviewed the topic of transvaginal placement of mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. There is no justification for any restriction for mesh placed abdominally (i.e. mesh sacrocolpopexy, including laparoscopic and robotic approaches) for the treatment of prolapse. “ quoted from the AUGS position statement linked above

The most important thing to note is that the concerns and subsequent restrictions were placed on Transvaginal Mesh Kits to treat prolapse, NOT abdominal mesh such as with the sacralcolpopexy procedure which has years and years of safety and results behind it. The concerns and subsequent restrictions were concerning the Vaginal Mesh Kits (ie Transvaginal Mesh Kits) that were released in the mid-2000’s and subsequently had high rates of complications associated with them. Most of these kits are no longer available or in use today because of these complications and restrictions.

Surgical Procedure – Abdominal Mesh Sacralcolpopexy

The procedure may be completed abdominally through a large incision, or more commonly now, through a minimally invasive approach with laparoscopic or robotic surgery. Both the laparoscopic and robotic approach to mesh sacralcolpopexy is completed on an outpatient basis with the use of mini-incisions in the abdomen. The laparoscopic/robotic approach has the advantage of a shorter hospital stay, less post-operative pain, faster recovery and decreased risks of infection compared to an open abdominal incision. The procedure should be completed exactly the same, no matter what approach is utilized, to ensure the same outcomes, cure rates and risk profile. Although the procedure has not changed much over the years, the mesh has improved. Standard type-I monofilament polypropylene has been utilized for many years as this has been shown to have the best outcomes, however the weight of the mesh has decreased significantly over recent years and now considered a light-weight mesh. The mesh is much softer, lighter and more flexible which has resulted in decreased complications such as mesh exposure and rates of pain with intercourse, however the cure rates have stayed the same. Most mesh that is now utilized is 25 gms/m2 or less. Pore size has also increased over the years resulting in better tissue in-growth and a more physiologic response by the body.

The procedure is started by placing a probe in the vagina and elevating the vagina up into the pelvis. The bladder and rectum are then dissected away from the vagina and a Y-shape mesh is placed over the top of the vagina. Typically, the posterior mesh arm is slightly longer than the anterior mesh that goes under the bladder on the anterior vaginal wall. The mesh is then attached to the vagina with mulitiple sutures on both the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. The long arm of the mesh is then attached up to the pre-sacral ligament (this is a very strong ligament on the sacral prominotory or the top of the sacrum/tailbone). The peritoneum in the pelvis is opened, the bowel and ureter held in a safe distance away, and the ligament on the sacrum is dissected and cleaned off. The vagina is then held in a natural position in the pelvis by an assistant holding a probe in the vagina from below and the long arm of the mesh then attached to the ligament. The mesh is placed so it is not too tight and allows the vagina to move in a natural, physiologic way. The mesh is then covered back over with the pelvic peritoneum so that it is not exposed in the pelvis and the bladder and rectum checked to ensure no injuries have occurred. Other prolapse procedures (such as a cystocele or rectocele) or incontinence procedures can be completed following the sacral colpopexy.

Illustrations of Mesh Sacralcolpopexy here

Risks of Mesh Sacralcolpopexy

Risks of abdominal/laparoscopic/robotic sacralcolpopexy are similar to any other vault suspension procedure, however do have some increased risks with the use of an implant, ie the polypropylene mesh. The benefit of having a higher cure rate with the use of mesh in more severe prolapse cases, seems to outweigh the risks of the use of the mesh, however all patients should be aware of these risks. Risks unique to the use of mesh in the procedure include risk of mesh extrusion (ie exposure of the mesh through the vagina) which is in the rate of 1-3%. This may have a higher risk of happening when the procedure is completed at the same time of hysterectomy as there is an incision at the top of the vagina which the mesh is then placed over. If this does occur, it typically is not a major complication, as the treatment in many times is either vaginal estrogen treatment alone, or a minor procedure to excise the expose mesh repair the small defect in the vagina in the area. Risk of erosion of the mesh into the bladder or bowel has been reported but is very rare and much <1% , but if did occur the mesh would need to be surgically removed from that organ.

Risks of infection or rejection of the material is very, very rare and in the range of <1%. If an infection in the pelvis does occur, most of the time this can be treated with the use of antibiotics and drainage alone and the mesh does not need removed. If the infection did not improve, then the implant would need to be removed. Pain with or without intercourse can occur with any prolapse procedure, and the risk does not increase with the use of mesh with sacralcolpopexy for vault suspension. If it does occur and does not improve with time or conservative treatment, then the mesh may need to be revised or removed and again this can typically be done by laparoscopically or robotically by experienced surgeons. Risk of tailbone or sacral pain is very low and typically treated by anti-inflammatory agents. Risk of infection to the pre-sacral ligament or infection of the bone or vertebral disc in the region is also very, very rare, but has been reported in a few cases in the literature. Bowel dysfunction in the form of constipation can occasionally occur, as can bladder dysfunction in the form of urgency/frequency or leakage could also occasionally occur.

Post-operative course

Hospital stay with the laparoscopic/robotic sacralcolpopexy is typically 24 hours or less and the recovery is similar to other laparoscopic/robotic surgery discussed in this website. Recovery at home is typically fairly rapid with the return to most normal activities in a few days to a week. Most surgeons place lifting, straining and exercise restrictions on patients during the healing phase of 6-12 weeks. Return to most activities, even athletic and vigorous ones, can be achieved following the procedure. Sexual function is also restricted for a period of time following the surgery. Depending on the type of work the patient does, return to work may be as quick as 1 week (ie sitting job) or as long as 12 weeks if required to do heavy lifting at work.

Overall, the mesh sacralcolpopexy is one of the most studied procedures in Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery and has the the highest long-term cure rate for vaginal vault prolapse. When utilized for moderate/severe vaginal vault prolapse, the benefits do seem to clearly outweigh the risks of the procedure, but of course the patient should clearly understand all risks and options.