What is a Cystocele?

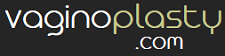

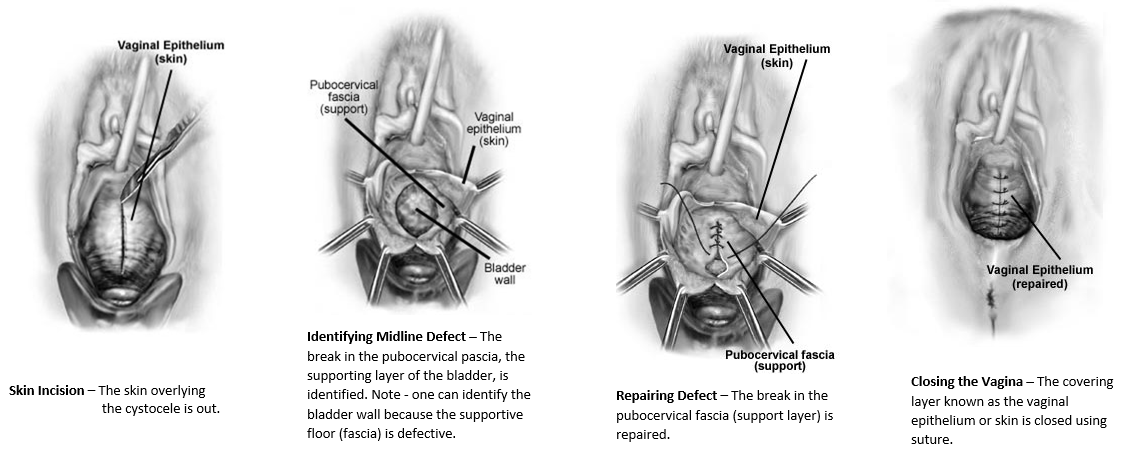

A cystocele is a form of pelvic organ prolapse in women and may also be called Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse secondary to the fact that the anterior or front wall of the vagina actually supports the bladder in the female. A cystocele is one of the most common forms of pelvic organ prolapse in women. The anterior vaginal wall forms a floor for the bladder to sit on and it goes from one side of the pelvis to the other and is attached to the pelvic floor muscles on each side. Damage to the connective tissue of the anterior vaginal wall from vaginal childbirth and/or aging is thought to be the cause of a cystocele. The anterior vaginal wall can actually tear away from its connection to the pelvic muscles or the wall can stretch out, both causing the bladder to drop and balloon into or out of the vagina.

What symptoms does a cystocele cause?

A cystocele is also commonly referred to as a dropped bladder and may cause symptoms such as feeling a bulge in the vagina or a bulge actually coming out of the vagina. This may cause a woman to feel pressure and/or discomfort in the vagina or pelvis. If it is large enough and is actually bulging out of the woman on a regular basis, the vaginal wall that is protruding can acutally get irritated or broken down and ulcerated from rubbing on her underwear. This is very uncomfortable for the woman to even walk or do her daily activities. A woman may also suffer from urinary symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency and/or urinary leakage/ incontinence. Urinary leakage may be the Stress Urinary Incontinence type, which is leakage with physical activities such as laugh, cough, sneeze, jumping, exercise etc. This is caused by a loss of support of the bladder neck and urethra which commonly occurs at the same time as cystocele. Urge incontinence can also occur with cystocele. This is the type of leakage that happens when a woman gets the urge to urinate but can’t get to the bathroom in time and leaks on the way. Urge leakage is caused by bladder spasms which seems to be secondary to the bladder falling and not being in its normal position.

Treatment for Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse / Cystocele

If the cystocele prolapse is mild and not causing any symptoms, it can just be monitored and observed until it starts causing symptoms. Conservative or non-surgical therapy includes pelvic floor physical therapy which includes specialized training in Kegel or pelvic floor muscle exercises, electric stimulation, biofeedback, bladder training and other treatment modalities that can help reduce symptoms, however will not cure prolapse. Another non-surgical option is a pessary. A pessary is a rubber or silicone donut shaped device that is placed inside of the vagina to support the prolapse. It must be big enough to stay in the vagina and support the prolapse, but not too big to cause discomfort. Most women use pessaries as a temporary solution to the prolapse or if their health is too poor for surgical correction.

Surgical Treatment of Cystocele

Depending on the size of the cystocele and what other prolapse may be present (it is very rare to just have a cystocele by itself, ie typically there are other organs falling at same time such as the uterus that must be treated at same time), surgical options vary by the experience of the surgeon. A surgeon should be experienced and an expert in Urogynecology and Female Urology surgery to be able to identify other defects in pelvic support and then utilize the appropriate surgical treatments to achieve the best cure rate for the patient. Cure rates are dependent not just on the treatment of the cystocele, but also the support at the apex of the vagina, ie treating vault prolapse or uterine prolapse at the same time. It has been shown that treating the top of the vagina or the apex increases cure rates of the anterior compartment at the same time.

Vaginal Approach

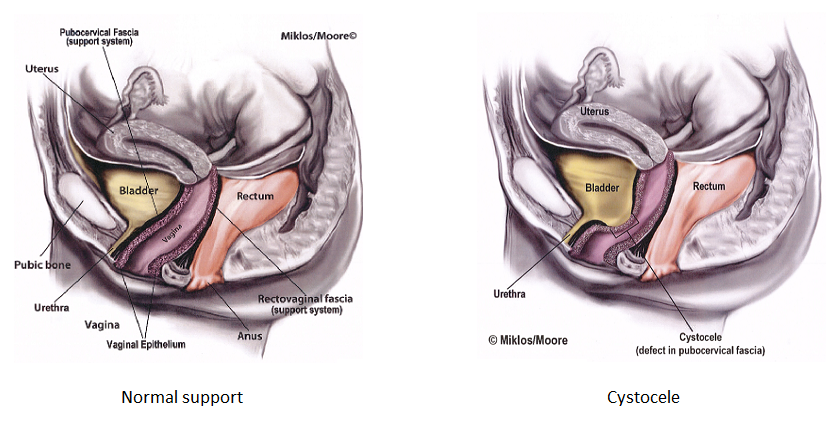

The vaginal approach to treat a cystocele is called an Anterior Repair or Anterior Colporrhaphy. This procedure is done vaginally, i.e. the abdomen does not need to be entered. The procedure can be done under regional anesthesia, such as a spinal, epidural or general anesthesia. In some cases, it can be completed under local anesthesia, with mild sedation, in women that have health issues and can’t tolerate general anesthesia or just want to avoid it.

The procedure is typically started with the surgeon injecting the anterior vaginal wall with a local anesthetic solution and then making an incision in the middle of the anterior vaginal wall or cystocele from the bladder neck (where the urethra or pee tube ends and the bladder begins) up to the top of the vagina or the uterus. The vaginal wall is then dissected off the underlying fascia of the bladder that is stretched out or torn (which is the cause of the bladder dropping or falling). The dissection is taken out to the pelvic sidewall muscles and then the fascia is plicated in the midline with interrupted sutures and this puts the bladder back up in its normal anatomic position. The defects in the fascia are repaired and the fascia tightened where was stretched out. This is why the procedure has been called traditionally a “bladder tack” in the past. The excess stretched out vaginal skin is excised and the vaginal incision is then closed with sutures that dissolve.

A cystoscopy (looking into the bladder with a camera) is usually completed at the end of the exam to ensure no damage was done to the tubes that connect the bladder to the kidneys or to the bladder itself. If the woman also has stress urinary leakage, ie leakage with laugh, cough, sneeze or other physical events, a sling procedure can also be completed at the same time through a vaginal approach. Again, it is vital to ensure that the uterus or the top of the vagina is supported well also, which may require another procedure. Vaginal approach to vault prolapse is usually completed with a Sacrospinous ligament suspension (SSL).

May be used vaginally to help support the bladder as well, however it typically is only used by very experienced surgeons and in women that have had multiple failures and cannot tolerate an abdominal approach to prolapse repair. Studies have shown it may be beneficial in certain situations, however it is vital to have a very experienced vaginal reconstructive surgeon (Urogynecology, Urology, Gynecology) , that also has extensive experience utilizing vaginal mesh

A laparoscopic or abdominal approach may also be utilized to repair a cystocele. This is called a Paravaginal defect repair. This is an ideal procedure to use if the woman also has Uterine prolapse or vault prolapse that needs repaired at the same time of the cystocele. A hysterectomy with a vault suspension procedure may be completed first laparoscopically (the vault may be suspended with the patients own uterosacral ligaments or with mesh via a laparoscopic or robotic sacralcolpopexy). The bladder can then be suspended by repairing the lateral defects where the anterior vaginal wall has torn away from the pelvic floor muscles. By repairing these tears or defects, this re-supports the bladder and places it in its normal anatomic position. If the patient suffers from stress urinary leakage, this can then also be repaired at the same time with a Burch procedure (a non-mesh procedure using sutures to support the urethra and bladder neck) or a sling procedure done vaginally. For more details on the surgical treatment of Stress (both mesh and non-mesh approaches) please click here.

Cure rates for either the vaginal or abdominal approach are in the range of 80-90%. Many of the failures may actually be secondary to the apex or top of the vagina not being supported at the same time. Urinary symptoms of urgency and frequency typically improve in up to 75% of women, however some women still need treatment with overactive bladder medication after surgery. As with any surgery, there are risks, however repair of a cystocele is a relatively low risk surgical procedure. Risks include injury to the bladder, urethra or tubes to the kidneys (ureters) but these are typically very rare and in the range of less than 1%. These type of injuries usually are recognized at the time of surgery and repaired by the surgeon at time of surgery. Other risks including bleeding requiring transfusion (<1%), worsening urinary urgency/frequency or leakage (1-2%), pain with intercourse (1-3%) , hematoma or infection (<1%).

Cost of surgery is typically covered by insurance, therefore check with your insurance company regarding deductible, co-pays, etc.